With SXSW in full swing in Austin, it’s hard to avoid a generative pre-trained transformer chat. The technology behind ChatGPT isn’t new. It’s been around since Google engineers created the transformer deep learning model in 2017, so what’s the big deal?

The hoopla —and consternation—around OpenAI’s ChatGPT is due, in part, to its accessibility. Anyone with a web browser can access it, and with over a million active users, ChatGPT recently became the fastest-growing consumer application of all time.

GPT-3 was trained on 175 billion parameters, and the multimodal GPT-4 (March 16 launch date) can supposedly process information in text, images, audio, and video—in multiple languages.

Aside from its accessibility, ChatGPT is making waves with its impressive natural-language understanding. From a high level, there are two subtopics within natural-language processing: natural-language generation (NLG) and natural-language understanding (NLU). NLG describes a computer’s ability to write, and NLU describes a computer’s reading comprehension skills.

“A lot of people are talking about the the NLG part,” says Ramprakash Ramamoorthy, director of AI and machine learning at Zoho Labs, “but the natural language understanding part has been flawless and phenomenal.”

Despite the impressiveness of the most recent iteration of ChatGPT, many people are anxiety-ridden. I believe this anxiety is warranted, but not only because of job displacement, algorithmic biases, AI-powered cybersecurity attacks, and the propensity for disinformation and misinformation to spread at scale, quickly and convincingly. These concerns are valid; however, generative AI is particularly troublesome from a privacy perspective.

Before we have a collective panic attack, it’s important to note that we are in familiar territory. Nearly every new technology since recorded history—including books, electricity, radio, television, video games, smart phones, and social media—has instilled a panic in a large portion of the populace.

Taking a technological deterministic perspective, it’s easy to see how emerging technologies are quickly linked to societal problems. Sometimes, it’s necessary to invoke regulatory and legislative efforts to rein in an emerging technology; this unfortunately, is one of those times.

Current legislative efforts to rein in generative AI

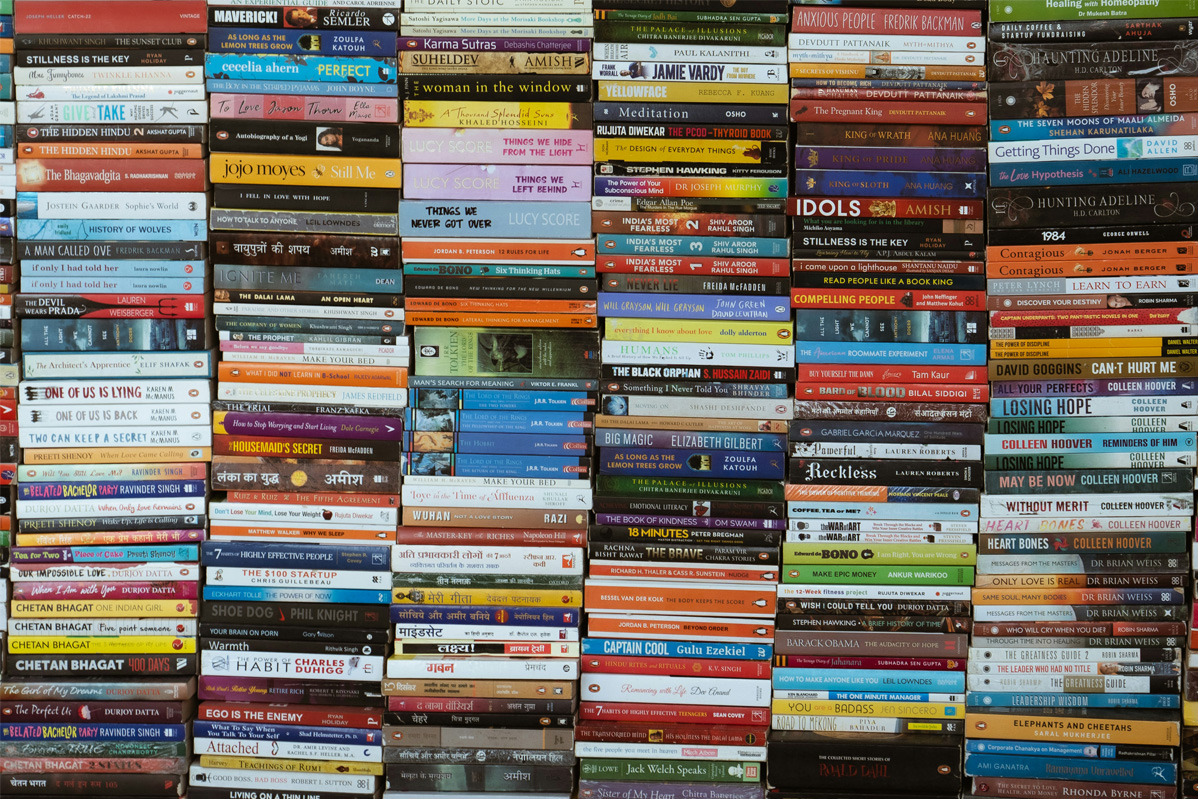

The European Union’s forthcoming AI Act has created a new category to account for generative AI systems. The EU’s legislative body hopes to pass its AI Act by the end of 2023. Also, we’re seeing a bevy of intellectual privacy lawsuits being filed against image-generation, code-generation, and text-generation AI models.

Copyright owners v. Microsoft, Microsoft’s GitHub, OpenAI (Doe v. GitHub)

Back in November 2022, two anonymous plaintiffs sued Microsoft for using open-source code with restrictive licenses to train their code-generation tool, Copilot. An adaptation of ChatGPT-3, Github’s Copilot is trained on billions of lines of public code; the plaintiffs argue that this violates copyright law. They are seeking $9 billion in damages.

Visual artists v. Stability AI (Andersen v. Stability AI)

In January 2023, three visual artists filed a class action suit against DeviantArt, Midjourney, and Stability AI’s image-generation models. The artists argue that these companies’ generative AI systems are engaging in copyright infringement, as the companies are using these artists’ work to train the AI models—all without consent or compensation to the artists. In the U.S., the defendants’ attorneys will likely argue that the use of the copyrighted art is allowed under fair use.

Getty Images v. Stability AI

Last month, Getty Images sued Stability AI, accusing the company of violating copyrights while using millions of Getty Images’ resources to train the Stability Diffusion image-generation model.

These copyright lawsuits are the tip of the iceberg—just wait until the data privacy suits start raining down. Speaking to Computer Weekly, Brighton, UK-based data protection writer Robert Bateman says,

“Publicly available data is still personal data under the GDPR and other data protection and privacy laws, so you still need a legal basis for processing it. The problem is, I don’t know how much these companies have thought about that…I think it’s a bit of a legal time bomb.”

Under GDPR, one needs a legitimate legal basis for processing personal information, even if that information is publicly available.

The need for generative AI regulation

If we care about privacy in the slightest, we are going to need generative AI regulation. In all likelihood, the U.S. will lag behind the E.U. on this front, much like we’ve seen with data privacy and GDPR.

The privacy concerns are myriad. To begin with, ChatGPT scrapes millions of webpages for its training data. Among these pages are hundreds of billions of words, many of which are copyrighted, proprietary, and comprised of personal data. Even if this personal data is publicly available (e.g., a phone number on a digital CV), there’s still the issue of contextual integrity—an increasingly important privacy benchmark that says that an individual’s personal data shouldn’t be revealed outside of the initial context it was given.

Moreover, until two weeks ago, OpenAI automatically incorporated all the data from its user prompts into ChatGPT’s corpus of training data. While interacting with ChatGPT-3 in mid-February, Duke Law professor Nita Farahany received the following message:

“Information provided to me during an interaction should be considered public, not private, as I am not a secure platform for transmitting sensitive or personal information. I am not able to ensure the security or confidentiality of any information exchanged during those interactions, and the conversations may be stored and used for research and training purposes.”

Due to the backlash that followed, as of March 1, OpenAI no longer uses data submitted through its API for model training—although users can still opt in to provide their data to OpenAI.

Okay, great. But what would prevent a user from opting in, then uploading someone’s personal information into the prompts? Are we able to ask OpenAI to remove our personal information? Can we ask OpenAI to fix inaccurate personal information it has collected? Unless we live in California or Europe, the answer is likely “no.” And even if we do live in California or Europe, the answer might still be “no.”

Speaking with the IAPP, Jennifer King, a privacy and data policy fellow at Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, explains,

“Certainly, they are crawling a lot of data, and when I talk to our computer scientists working on machine learning, I hear [it’s] a kind of Wild West. There’s a lot of data being crawled, and there’s not necessarily practices, policies, procedures, documentation in place to know where things are coming from.”

OpenAI seems to be making things up as they go along. While OpenAI’s privacy policy is changing, it’s important to remember that this is a for-profit entity. OpenAI—like Meta, Google, and others in the generative AI arms race—is going to eventually need to make money somehow, and that very well may come from selling user data to third parties.

Even OpenAI CTO Mira Murati thinks the technology needs to be regulated. When asked whether she believed government intervention was appropriate, Murati said, “We’re a small group of people and we need a ton more input in this system, and a lot more input that goes beyond the technologies—definitely regulators and governments and everyone else.”

But let’s not just pick on OpenAI. Most, if not all, of the companies racing to be first to market in the generative AI race have historically not had much concern for user data privacy. In the text-generation space alone, there’s Google (Bard), Meta (LlAma), Baidu (Ernie); DeepMind (Sparrow), and OpenAI (ChatGPT). Make of that cast of characters what you will.

A quick caveat

Generative AI—be it in the form of an AI-powered chatbot, a synthetic video, or a deepfake audio file—isn’t inherently bad. There are many positive use cases for such technologies; as a quick example, researchers are exploring the use of neural networks and synthetic audio to help ALS patients’ speech.

Key takeaway

The generative AI arms race is about to invade our privacy. To be sure, generative AI poses other threats that we’ll talk about down the road, including job displacement, AI-powered cyberattacks, and the proliferation of convincing misinformation; however, for now, I hope that regulators, legislators, and tech workers are cognizant of the privacy dangers that generative AI poses.