In the wake of the ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline, President Biden issued an executive order and called upon the U.S. Senate to quickly confirm his nominees for National Cyber Director and Director of the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency—Chris Inglis and Jen Easterly, respectively. Inglis and Easterly, both former NSA operatives, will be tasked with protecting state and federal networks from ransomware attacks, among other things.

In his remarks on the Colonial Pipeline incident, Biden vowed to make the fight against ransomware a priority. Biden said, “Our Justice Department has launched a new task force dedicated to prosecuting ransomware hackers to the full extent of the law. And, let me say that this [Colonial] event is providing an urgent reminder of why we need to harden our infrastructure and make it more resilient against all threats.”

On the cybersecurity battlefield, Biden wants to see far more collaboration between the government and the private sector. As he explained, “I signed an executive order to improve the nation’s cybersecurity. It calls for federal agencies to work more closely with the private sector to share information, strengthen cybersecurity practices, and deploy technologies that increase reliance against cyberattacks.”

For the moment, it seems as if the quick response has been somewhat effective. DarkSide, the Ransomware-as-a-Service (RaaS) syndicate responsible for the May 7 attack on Colonial Pipeline, has gone dark. Two other ransomware groups, AKO and Everest, have followed suit, and other RaaS organizations, such as Avaddon and REvil, have issued statements saying they will abstain from targeting government, healthcare, and nonprofit organizations. However, taking cybercriminal syndicates at their word is rather absurd. After all, DarkSide had promised not to target government infrastructure in the past as well.

So, why did DarkSide target Colonial Pipeline in the first place?

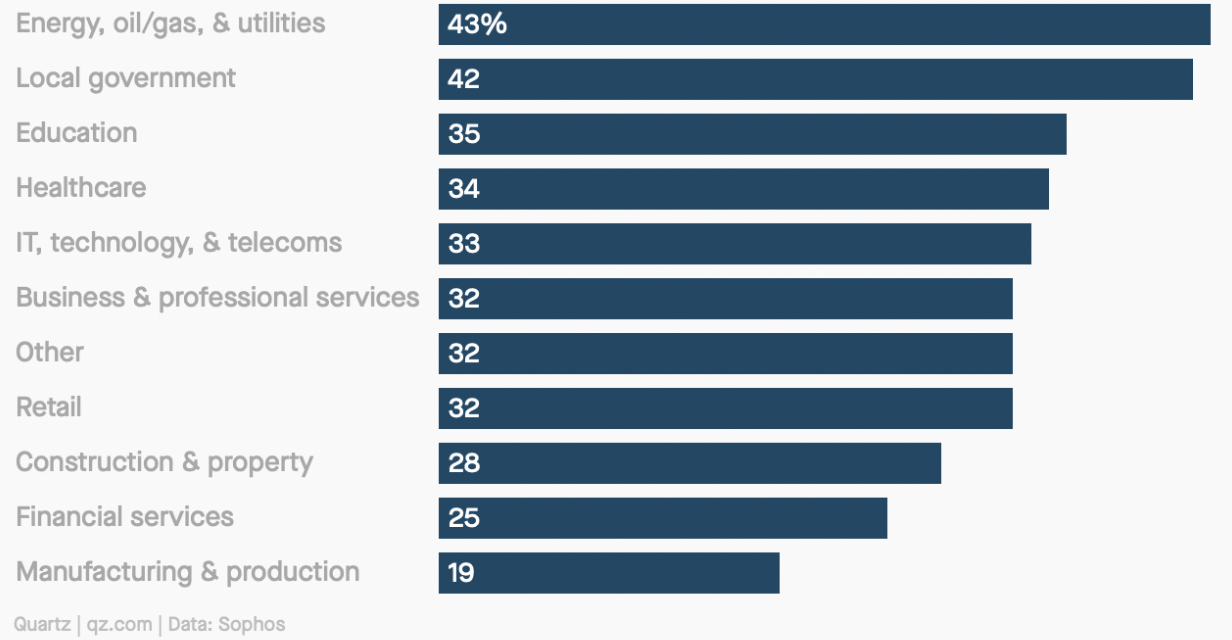

Energy companies are frequent targets, as they’re statistically the most likely to pay the ransom.

Many critical infrastructure systems tend to be older, and some were originally designed without robust security in mind. However, even more importantly, these companies are under immense pressure to maintain service. This fact alone makes such companies prime targets for ransomware attacks. Also, energy companies are more likely to pay ransoms. In a survey of 5,400 companies across the globe, Sophos researchers found that the energy sector was the most likely to pay up in the event of a ransomware attack.

Percentage of companies that paid the ransom after being hit by a ransomware attack in 2020, by sector

As a caveat, it’s not only ransomware attacks that can send energy companies into a frenzy. Given that there are serious repercussions if supply chains are disrupted, energy companies have been known to succumb to well-orchestrated social engineering and phishing scams as well.

For example, in March 2019, the CEO of a U.K.-based energy firm fell victim to a deepfake audio attack, in which he was duped into transferring $234,000 to a Hungarian supplier. From there, the funds were transferred by criminals to a bank account in Mexico, and then dispersed to various locations across the globe. This was admittedly a rather brazen and unusual voice-spoofing attack; however, it’s not so surprising that the cybercriminals decided to target the energy sector in that case.

Where does the RaaS money go?

Generally speaking, RaaS organizations like DarkSide take between 20-30% of the acquired ransom. The other 70-80% goes to third-party affiliates—blackhat hackers—who gain access to a victim’s network and then deploy DarkSide’s ransomware. Working alongside law enforcement, Elliptic, a blockchain analysis firm, attempts to follow the Bitcoin ransom trail, and in this case, they were able to do so. According to their analysis of blockchain transactions, 75 BTC (a portion of the $5 million ransom paid out by Colonial Pipeline) went to a Bitcoin address; in fact, this was the same address that had received BTC from another ransomware attack on May 11.

The May 11 attack was conducted on Brenntag, a chemical distribution company. In this $4.4 million RaaS attack, hackers were able to gain access to Brenntag’s network after purchasing stolen credentials on the dark web. As an aside, it is unclear at this point exactly how hackers were able to breach the Colonial network. Nevertheless, Elliptic claims to have tracked 18% of the Colonial funds to smaller cryptocurrency exchanges, which should help law enforcement track down some of the perpetrators.

Is this the end of DarkSide?

Probably not. That said, some good things did come out of the horrific ransomware attack on the Colonial Pipeline. Ransomware-as-a-Service has become a household term on Capitol Hill, and strengthening the nation’s cybersecurity infrastructure is clearly a top priority for the Biden administration. That’s all positive.

However, the ransomware ecosystem is still alive and well, and it’s unlikely DarkSide is going gently into the good night. It is quite probable that they shut down their public-facing recruiting websites, in order to conduct an exit scam, whereby the group winds down its current operation, only to reemerge under a different shingle down the line. Nevertheless, forcing a RaaS group like DarkSide to go dark is a good first step in the long ransomware battle ahead.