Taking a cue from the food industry, IoT manufacturers should embrace privacy and security “nutrition labels,” as these labels will allow privacy-focused companies to differentiate themselves.

Consumers are eager for transparency in this space, and IoT manufacturers would be wise to embrace these labels before a government mandate arrives—and to be sure, government involvement is on the horizon.

The U.S. Cyberspace Solarium Commission (CSC), now operating as a non-profit, non-governmental organization, has been tasked with “establish[ing] a national cybersecurity certification and labeling authority.” Initially created to assist critical infrastructure providers’ technology procurement decisions, this cybersecurity labeling program will affect much of the consumer products sector.

It remains to be seen what this labeling program will look like. In October 2022, the CSC met with roughly 50 representatives from academia, NGOs, and the private sector. At this workshop, there were some of the usual suspects—Amazon, Comcast, Google, Intel, LG, Samsung, Sony, Consumer Reports—and of course, various lobbying groups.

After the summit, a White House official said the IoT device ratings may be based on cybersecurity elements, such as vulnerability remediation, whether data is encrypted, and interoperability with other products; however, it will surely include privacy elements, including whether data has been collected on consumers.

According to reporting from CyberScoop, a policy member from the R Street Institute left the summit believing that “more extensive privacy standards around data collection and sharing could be considered as part of the ratings system down the road.”

Without a doubt, this IoT device privacy labeling initiative owes a debt to important work from Carnegie Mellon University. In fact, CMU researcher Yuvraj Agarwal was in attendance at the summit.

The Carnegie Mellon CyLab Security and Privacy Institute

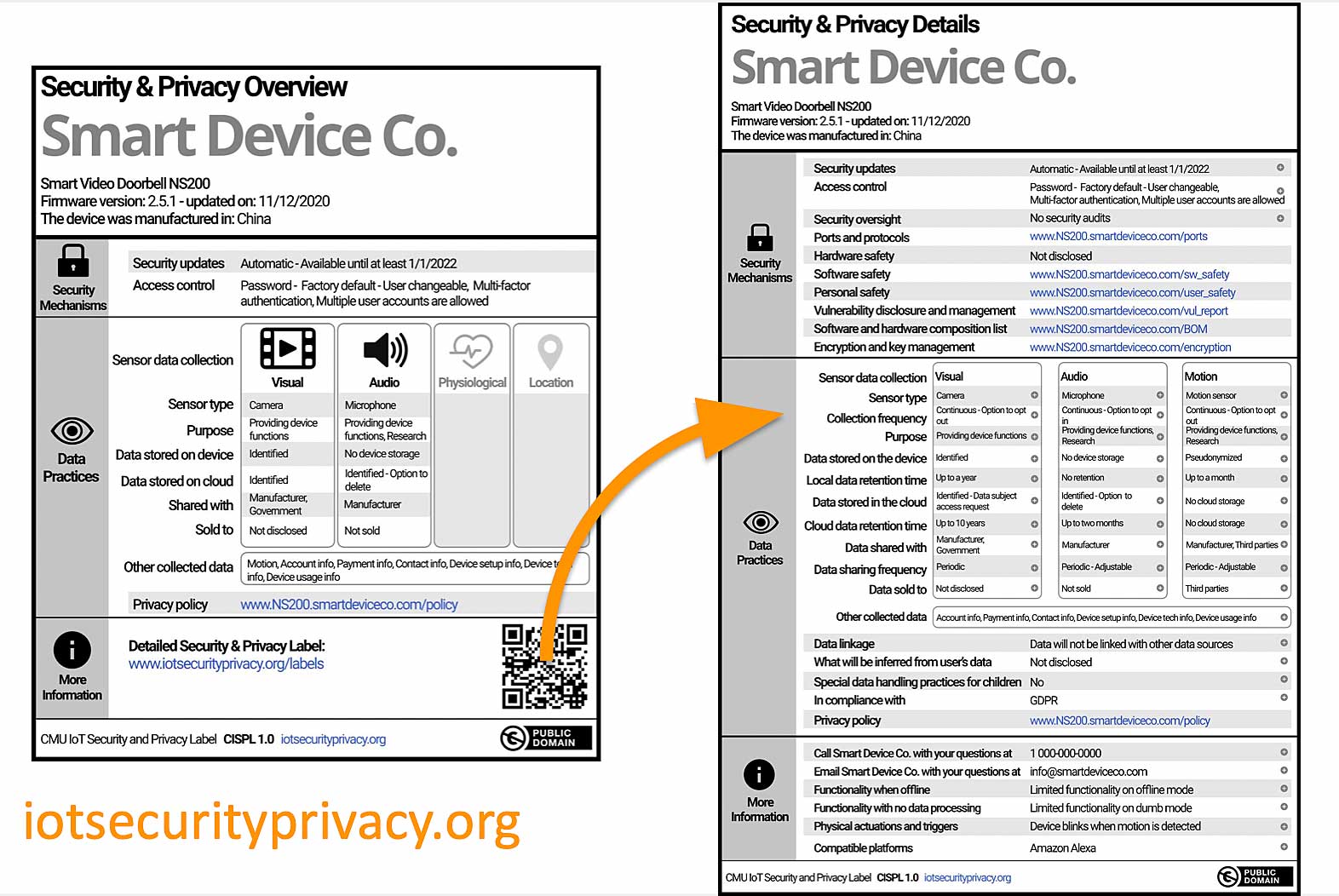

After four years of research, Pardis Emami-Naeni, Yuvraj Agarwal, Lorrie Cranor, and their colleagues have created a robust prototype of a nutrition label for IoT devices.

Made up of 47 different privacy, security, and general attributes, the prototype has two layers. The first layer, which is designed to be displayed prominently on the product package, is aimed at everyday consumers. The second layer, available online via a link or QR code, is aimed at software engineers or knowledgeable consumers seeking more detailed information.

The CMU researchers didn’t come up with this nutrition label out of a vacuum. It’s the result of the four studies below.

“Exploring how privacy and security factor into IoT device purchase behavior” 1/2019

The researchers found that privacy and security were among the most important factors that consumers consider when purchasing an IoT device. In fact, privacy and security are the most important factors, after features and price.

“Ask the experts: What should be on an IoT privacy and security label?” 12/2019

In this study, the researchers interviewed 22 privacy and security experts to ascertain what exactly to include in their label. There were experts from academia, NGOs, government, and of course various entities within the tech world, including several working in policy roles at hardware and software companies.

“Which privacy and security attributes most impact consumers’ risk perception and willingness to purchase IoT devices?” 6/2021

To improve their label design, this study helped the researchers learn which privacy and security label attributes influence consumer risk perception and willingness to purchase. The researchers learned that consumers were more willing to buy products when they knew their information wouldn’t be retained or shared with third parties.

As Emami-Naeini et al. write, “Participants frequently expressed concerns about not knowing how their information would be used if it was shared with or sold to third parties.”

“Are consumers willing to pay for security and privacy of IoT devices?” 10/2022

Through this study, the researchers learned that, yes, consumers are willing to pay a significant premium for security and privacy.

Given that privacy and security are admittedly related, it’s perhaps unsurprising that there was a lack of consensus as to whether or not privacy and security attributes should be presented in separate sections. Half of the experts felt separate sections were appropriate, and the other half wanted to combine them into one section.

An examination of the relationship between security and privacy

Through the course of these studies, there was quibbling among experts about the difference between privacy and security. Some believed that security was easier to quantify, and that privacy was more contextual and subjective.

As Emami-Naeini et al. write, “When defining security, almost all experts (21 out of 22) mentioned the CIA triad of confidentiality, integrity, and availability. However, experts had different definitions for privacy. Some experts (9 out of 22) defined privacy as having transparency and control over data practices and some experts defined privacy as the confidentiality aspect of security (8 out of 22).”

A few experts pointed out that privacy is inherently dependent upon individuals’ respective comfort levels and personal preferences. That’s technically true; however, the fact remains: it is quite simple to quantify privacy. Either a company is collecting consumers’ data or it is not. Companies either sell that data to third parties, or they do not. If companies are indeed collecting user data, they can gain consumer trust by explicitly laying out their methods and disclosing the reasons why they’re collecting user data in the first place.

Will we see security and privacy labels soon?

The ball is rolling, but the timetable for label adoption is unclear.

Voluntary label adoption seems unlikely, although CMU CyLab researchers believe that label adoption could come from retailers.

Cranor et al. write, “Retailers could incentivize adoption by requiring manufacturers of products they sell to label their products, or even by promoting labeled products; for example, by placing them at the top of search results.”

Now, big box stores, like Best Buy, certainly could refuse to carry IoT devices if the manufacturers refused to carry the privacy label. However, this seems a bit far-fetched unless retailers find a financial incentivize to to do so.

To be fair, retailers could theoretically mandate that IoT manufacturers place privacy/security labels on their packages. It’s not without precedent.

We’ve seen this with application developers and online app marketplaces

In December 2020, Apple famously began requiring that all applications in its App Store disclose data collection practices. To use the App Store, Apple required all third-party apps to disclose what type of data the app collects and whether that data is used to track users.

Shortly after Apple’s privacy nutrition label launch, Google followed suit with its own label initiative for Google Play.

A quick caveat: Washington Post tech columnist Geoffrey Fowler pointed out that Apple doesn’t immediately verify that the third-party apps’ privacy information on the Apple App Store is accurate. On the labels, there is a disclaimer that reads, “The developer indicated that the app’s privacy practices may include handling of data as described below. This information has not been verified by Apple.” Thus, even with Apple’s intervention, the nutrition label content is still based upon developer self-reporting, at least initially.

Like online marketplaces (e.g., Google Data Safety and Apple Privacy Nutrition), retailers could intervene and mandate that IoT manufacturers use privacy labels; however, the far more likely scenario is that widespread adoption of IoT privacy labels will come from a government mandate.

Another caveat: It’s worth emphasizing that these labels won’t be forced upon IoT manufacturers. All labels will be voluntary in nature.

The current state of security and privacy label legislation

Senator Ed Markey and Congressman Ted Lieu have been trying to get an IoT device certification law passed for years. Although their Cyber Shield Act never received a vote on the House or Senate floor in 2017 or 2019, they reintroduced the bill in March 2021.

According to the language in the bill, The Shield Act “requires the Department of Commerce to establish the Cyber Shield Program, a voluntary program to identify and certify covered products. These products are consumer-facing physical objects that meet industry-leading cybersecurity and data security benchmarks and that can (1) connect to the internet; and (2) collect, send, or receive data or control the actions of a physical object or system.”

Although unlikely to pass, the content within the Shield Act of 2021 is influencing the White House and CSC. Directly after the October 2022 White House workshop, Ed Markey’s camp issued a press release, praising the work toward what Markey describes as an “Internet of Things cyber label.”

According to the release, “As Americans install tens of millions of internet-connected devices for their homes, cybersecurity protections have never been more important. That’s why we introduced the Cyber Shield Act to create a voluntary consumer label indicating whether a device meets high cybersecurity benchmarks. We applaud the White House today on their announcement that they will adopt a similar approach and deliver a win for American families so that they have the information they need to safeguard their privacy at home. An Internet of Things cyber label is a critical step to returning power to consumers and strengthening cybersecurity protections.”

We’ll have to wait and see if this voluntary IoT label program ever comes to fruition; however, the ball does appear to be rolling.

Key takeaways

IoT privacy nutrition labels are coming down the pike; however, they will be voluntary at first. Keeping it voluntary isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Consumers will be certainly take notice of IoT manufacturers who opt not to use the labels.

If the privacy labels work as intended, IoT device manufacturers—and likely other industries—will be forced to compete on privacy and security, which is a net positive for consumers. Also, journalists will increasingly cover the security/privacy of specific devices, which will further drive consumer awareness.

Also, even if many consumers are initially confused by the labels, this will change over time. After all, we take food nutrition labels for granted today, when we go to the grocery store.

When mandatory food nutrition labeling came on the scene back in 1990 (the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act), it surely was met with resistance from reluctant actors in the food industry. We can expect that this privacy labeling initiative will be met with some similar resistance. Nevertheless, companies that operate in good faith would certainly be wise to embrace this labeling effort. It can only help them stand out from the pack.