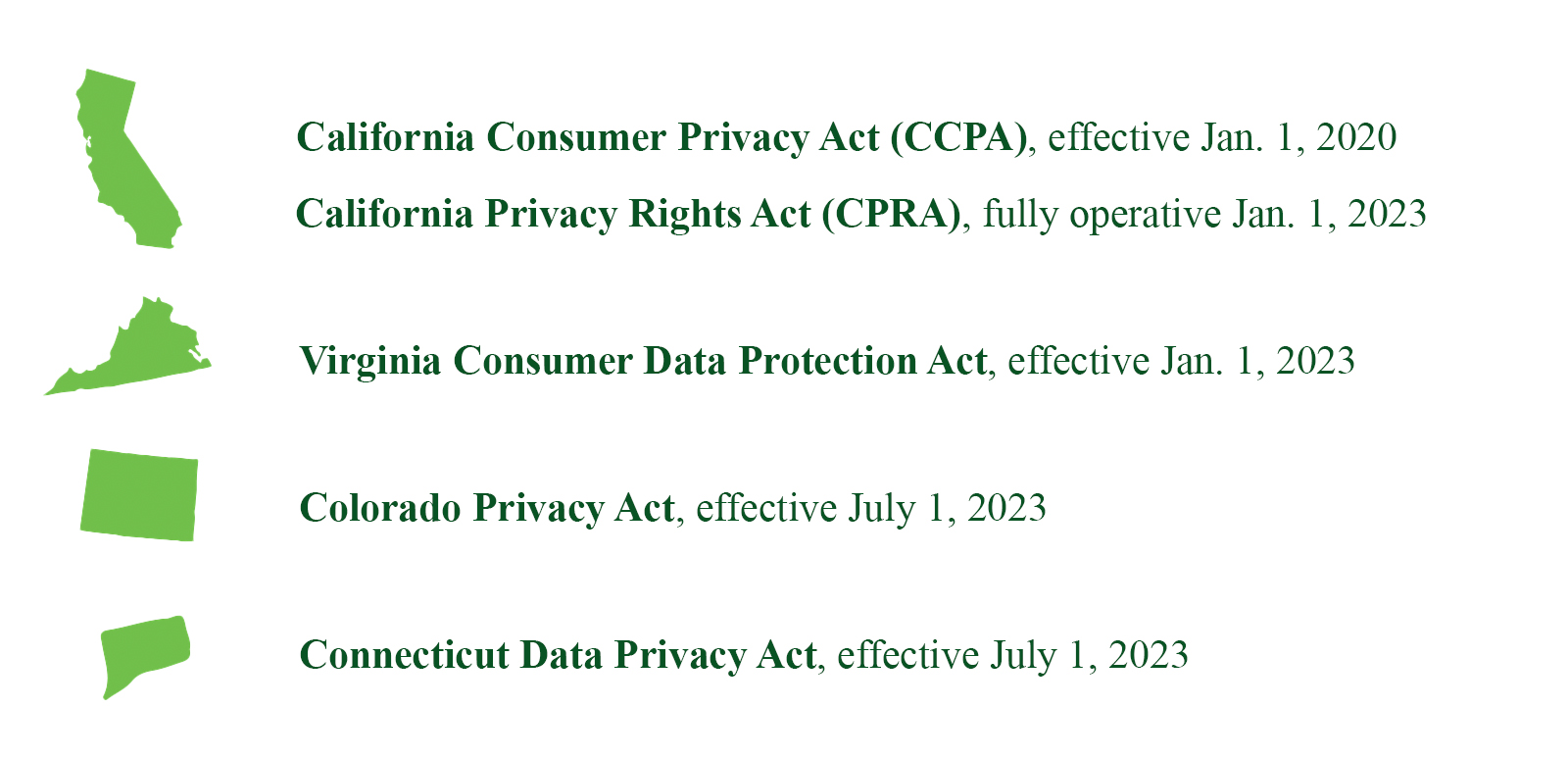

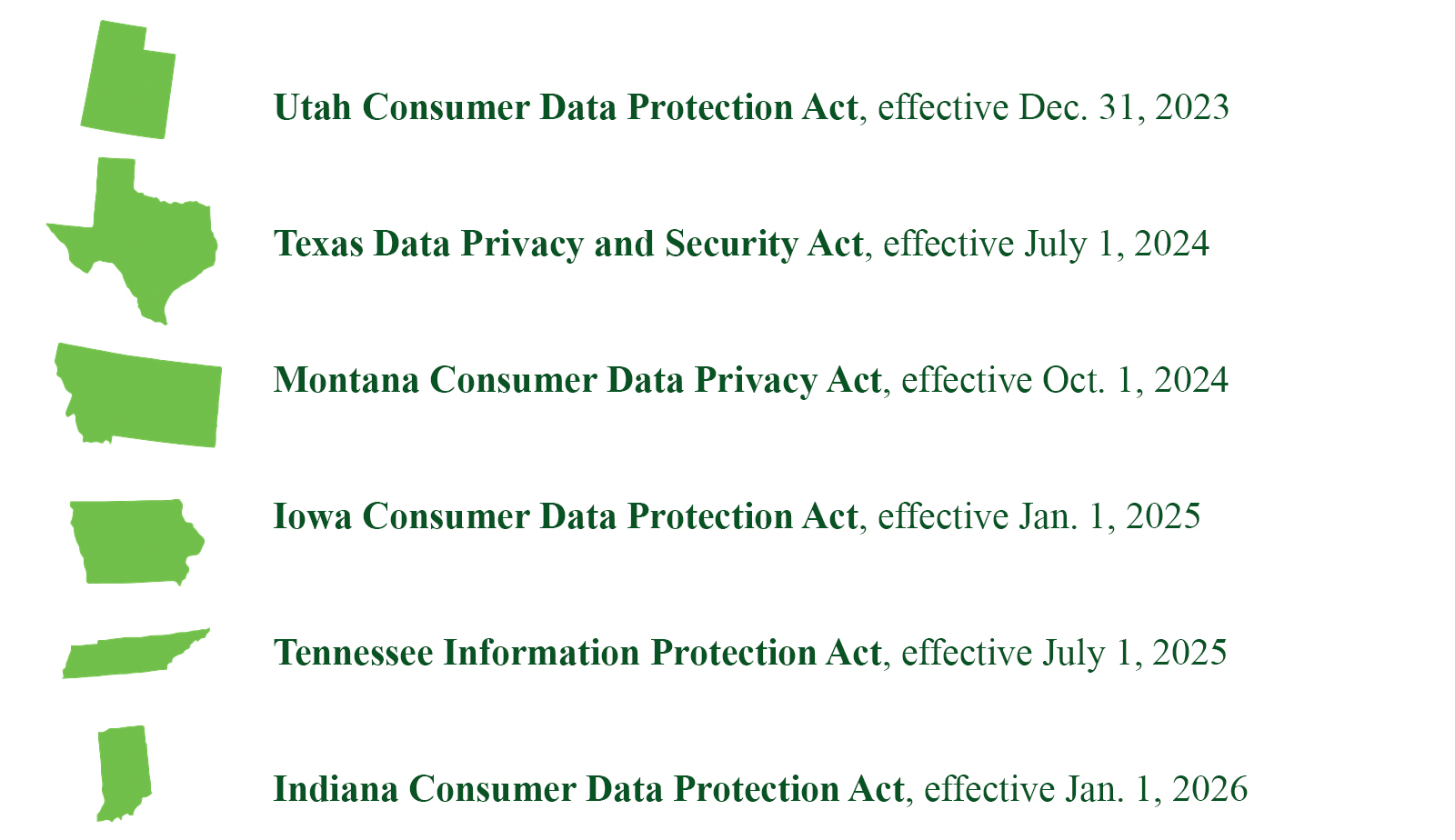

With a policy vacuum on Capitol Hill, there has been a flurry of state-level activity over the past year. Five more states passed laws in 2023, bringing the total number of state-level data privacy laws to ten.

California and Virginia already have operative data privacy laws, and on July 1, laws from two more states—Colorado and Connecticut—came into effect.

Six other states—Utah, Texas, Montana, Iowa, Tennessee, and Indiana—have passed laws; however, these have yet to take effect. Although these six states are all predominately red, each has different rules related to consumer rights and business obligations. In some cases, the differences are massive.

Take Montana, for example. According to recent reporting from Politico, Montana resisted a great deal of Big Tech lobbying. Despite complaints from the State Privacy and Security Coalition, Montana legislators refused to remove “universal opt-out requirements,” which essentially allow Montanans to opt-out of tracking with a single click. Additionally, Montana legislators refused to allow carve-outs for “pseudonymous data,” which would have allowed tech companies to continue to track consumers who have opted out.

Lobbyists advocated for a provision that would have provided companies with time to remedy a violation before accruing a fine; however, it was to no avail, as Republican Gov. Greg Gianforte and bill sponsor Sen. Daniel Zolnikov (R-MT) didn’t take the bait.

Speaking about the lobbyists’ attempts to get him to water down the bill, Zolnikov colorfully said, “I’m not an idiot, and you treating us in Montana like a bunch of rural backwoods folks is quite an insult as well.”

Suffice it to say, it is too simplistic to assume that blue-leaning states offer tougher consumer data privacy legislation than red-leaning states. In an effort to highlight the myriad differences between the states’ data privacy legislation, the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) provides an excellent chart of all the consumer privacy bills, which they update frequently. It shows the bills’ statuses: Introduced, In Committee, In Cross Chamber, In Cross Committee, Passed, and Signed.

Additionally, the chart highlights the states’ various, and varying, consumer rights—e.g., right to access; right to correct; right to delete; right to opt-out of certain processing; right to portability; right to opt-out of sales to third parties; right to opt-in for sensitive data processing; right against automated decision making, and private right of action, which is essentially the consumers’ right to seek civil damages for a business’ violation of the law.

IAPP’s chart also lists the state laws’ different business obligations—e.g., opt-in defaults, which require businesses to treat a consumer under a certain age with an opt-in default for the sale of his or her personal information; transparency requirements, risk assessments, and processing limitations.

Minimize your data collection, processing, and usage.

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that the best course of action would be to abstain from collecting, processing, trading, selling, and otherwise handling sensitive consumer data in the first place. If possible, you should comply with the most stringent laws (e.g., CPRA, GDPR) and adhere generally to the principle of data minimization, which states that one should only handle user data that is essential to the task at hand, and only for as long as that task takes.

However, not every company can completely abstain from processing consumer data. For such companies, here are a few ways to navigate the myriad data privacy laws in the states:

Identify which, if any, laws apply to your business.

Each state has a different threshold for companies doing business in its state. There are thresholds that pertain to the number of customers in the state, the percentage of revenue attributable to the sale of personal data, and a minimum number of customers.

For example, the Virginia law—which incidentally was based on a bill drafted by an Amazon lobbyist—only pertains to either (1.) businesses that have at least 100,000 customers in Virginia, or (2.) businesses that have at least 25,000 consumers and make at least 50 percent of its gross revenue from the sale of personal data. Also, if one’s business doesn’t have at least an annual revenue of $25 million, the Virginia law isn’t applicable.

Aside from these basic thresholds, there are many other ways in which a state’s law may not pertain to your business. States have different regulations related to the types of data that an organization is allowed to collect and how that data can be used.

Some states have processing loopholes; for example, laws in Iowa, Utah, and Indiana—some of the weakest in the country—have a rather broad definition of what it means to “sell” user data. If you’re not explicitly charging money for user data in those states, you’re likely in the clear.

Review your service contracts with third-party vendors; frequently update your internal and external privacy policies, and have an incident response plan in case of a cyberattack.

As a best practice, it’s prudent to build data protection clauses directly into the contracts you have with your third-party vendors. Even if it’s not required by law today, it may be down the road. You don’t want to be held liable for data protection mistakes made by your vendors. Also, when in doubt, put things in writing. Auditors—and regulators—need to see written procedures for information collecting practices. Also, have an incident response plan and ensure that your privacy policies are up-to-date and accurate.

Err on the side of caution, and look to California and Europe.

Of the ten state laws in the U.S., California is the most stringent; thus, you’re probably in compliance with the other state-level laws if you comply with the CPRA. However, every business operates differently; these laws are quite granular, and I’m not a lawyer. Thus, in the short term, be sure to have your chief security officer and legal team assess the ten laws.

In the long term, Congress will eventually pass a federal data privacy law. So, if you’re compliant with GDPR in 2023, you’ll most likely be all set by the time the federally mandated bill comes down the pike—whenever that may be.