This article series is here to help you hack productivity by optimizing the human factors that influence production and performance. The objective of this series, however, is to show that there’s no shortcut to an optimized worker. There are always systemic, cultural, and personal factors at play, influencing the quality and quantity of work accomplished. Although we don’t have a complete understanding of the conditions and constraints that influence every human’s mind, there are many lessons for leaders to integrate into their understanding of their workplace and those they lead.

Enterprises are increasingly reliant on their IT department to keep their operations running, so IT leaders should be particularly focused on and equipped to support their IT staff. While there’s plenty of strategy, advice, and intuition an IT leader needs to consider for their department’s long-term impact, the short term cannot be ignored. Certainly it’s the long-term considerations that place demands and constraints on what should be worked on in the short term, but the most pressing short-term consideration is whether the members of the IT department have the resources to get their work accomplished each day.

That short-term determination will change over time, and will be different for each role and each person who occupies that role. However, the consideration for resources and fulfillment of natural needs will ensure that the IT department remains resilient, ensuring the long-term survival of the whole organization.

That survival, however, is not guaranteed. Although a company isn’t a living being in the strictest sense, viewing a workplace through the lens of living processes can help you contextualize some of the driving forces behind productivity. Every organism has natural needs that must be met for it to survive. But organisms and organizations alike cannot rely on singular sources for fulfilling those needs, nor can they survive in the long term if the resources they have are disproportionately allocated.

As we’ll explore below, leaders need to consider the natural needs of their workforce. Utilizing wisdom, heuristics, and empathy, they can extrapolate these lessons to their entire organization.

Organizations as complex living systems

Much like how humans are comprised of cells, organs, and systems, so too are organizations made up of many interconnected parts. There’s a parallel between people and organizations when it comes to productivity: When natural needs are not met, productivity is diminished.

If conditions are lacking for long enough, the situation could require a disproportionate amount of effort to remedy. And in some cases, the poor conditions in a particular domain are destined to lead to death, and it’s only the support a person or organization receives in other domains that is keeping it alive. But a long, drawn-out death isn’t what we should be aiming for. In both people and organizations, we should be supporting the various domains needed for survival.

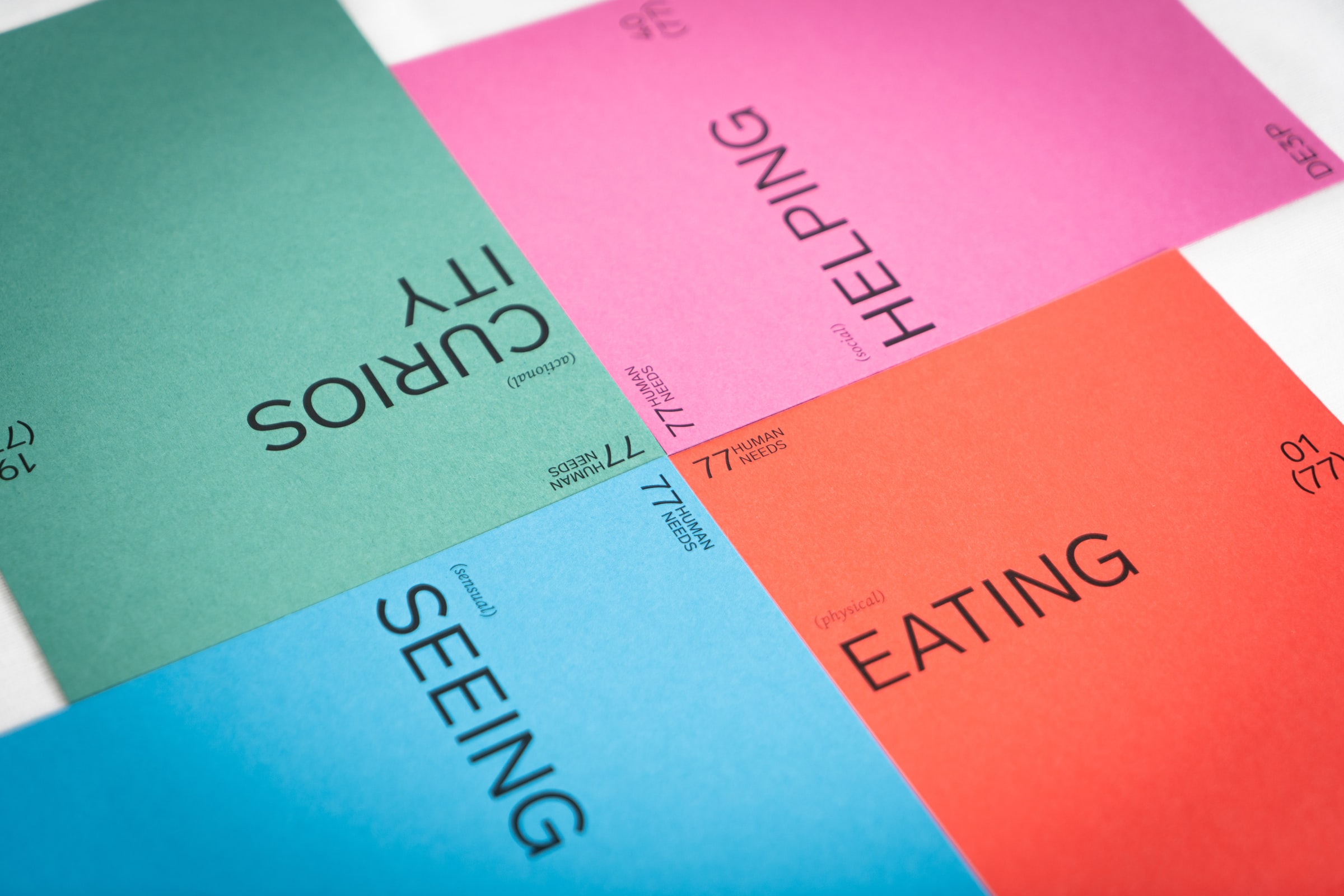

Satisfying natural needs

Abraham Maslow introduced his hierarchy of human needs nearly 80 years ago, and since then the concept has been popularized and expanded upon, although there have been some critiques over the years about the concept. His original proposition was based only on top performers and lacked empirical evidence. Additionally, there can be personal and cultural differences to the ordering, relevance, and applicability of each category of needs. Despite the criticism, the core principles have outgrown academic studies in psychology and sociology to become a driving force that informs teachings in the realm of business management.

For example, the Johnson & Johnson Human Performance Institute focuses on four dimensions for developing driven individuals: physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. These dimensions roughly translate to Maslow’s hierarchy, as do many other systems and iterations you’ve likely encountered.

Exploring the hierarchy of needs

As Maslow described it, the hierarchy is built on a foundation of deficiency needs, which provides people with greater motivation to satisfy them the longer a need is unmet. The better satisfied a lower need is met, the more likely an individual is motivated to satisfy a higher need.

1) Biological and physiological needs: The lowest-order needs are the most important and include the biological requirements for staying alive: food, drink, shelter, sleep. etc.

2) Safety needs: Security and safety arise when an individual is provided order and control, and a high degree of predictability. Different environments can support different safety needs, such as a family for emotional security, a community for social and property security, and a job for financial security.

3) Love and belonging needs: The ability to be intimate and trusting with others or affiliate with and feel like belonging to a group. Exchanging love and affection tends to come from family and friends, but interpersonal relationships can arise elsewhere.

4) Esteem needs: Esteem comes in two forms: self-esteem and social esteem. Esteem for oneself is met through dignity, achievement, mastery, and independence. Social esteem, the need to be accepted and valued by others, is met by gaining reputation and respect.

Above the deficiency needs stand the growth needs. Maslow’s original model presented only one growth need, self-actualization, which sat at the top of the hierarchy. His later work included additional needs that relate to one’s sense of being and growth. Unlike deficiency needs, the motivation to pursue growth needs can increase the better they are met.

5) Cognitive needs: The need for organizing experiences meaningfully. Cognitive needs arise from experiences that engage one’s sense of curiosity and exploration in a predictable, non-abstract way. Satisfying this need comes from the pursuit of knowledge and understanding, allowing one to verbalize meaning and reasoning.

6) Aesthetic needs: The need for aesthetics is satisfied by an appreciation and search for beauty. Observing one’s surroundings in nature and immersing oneself in experiences that provide balance, novelty, or aesthetically pleasing forms.

7) Self-actualization needs: Maslow said that this need is a desire “to become everything one is capable of becoming.” Satisfying this need comes from explicit motives such as realizing personal potential, seeking personal growth, and pursuing peak experiences.

8) Transcendence needs: This is the highest-order need and arises from a person holding values that extend beyond their sense of self. A person is motivated by transcendental needs when they pursue things like the betterment of humanity, a dedication to the service of others, or experiences that diminish the self in favor of nature, the cosmos, or a spiritual identity.

Maslow also pointed out in his later work that most behavior is motivated by multiple needs: “any behavior tends to be determined by several or all of the basic needs simultaneously rather than by only one of them.”

Utilizing Maslow’s hierarchy in the workplace

As much as possible, communicate with employees to see whether their basic needs are being met. Whenever possible, take an approach of transformative leadership, rather than transactional leadership

You want your employees to be productive, and if they’re engaged with their work, then they want to be productive too. But if their on-the-job motivations are constantly being detracted by deficiencies—things like insufficient sleep or a lack of security at home—then their performance will increasingly slip over time.

Even if you’re ensuring that employees’ lower-order needs are being met, many employees will still look for opportunities to self-actualize. If someone feels like their employment isn’t providing a sense of fulfillment and opportunities for mastery, autonomy, and respect, then they’ll eventually leave the organization to fulfill these needs. The way your company cultivates competency, collaboration, and culture should coincide with fulfillment of deficiency needs and engagement with growth needs.

Exploring Maslow’s hierarchy can help clarify why some people behave the way they do. For an organization that wants to optimize productivity, the advice is twofold:

- Set up each worker for a baseline of success by ensuring their deficiency needs are met. Provide opportunities for employees to express their needs in a genuine fashion and attempt to fulfill those needs without superficiality.

- Encourage each employee to rise above that baseline by providing fulfillment for their growth needs. This includes opportunities to grow their understanding and pursue a just cause.

Managing time, energy, or relationships?

The primary efforts of management should be to ensure that the right work is getting done each week. But does that mean focusing primarily on the hours scheduled for work? Does it mean honing in on the energy, bandwidth, and expected workload of their team? Or, does it mean calling on the available communication channels and strength of their interpersonal relationships?

Like many things in life, the answer likely changes from week to week, and depends on trends and unfolding developments. Not everything can be predicted and planned for. However, taking into account the previous articles in this series and a focus on natural needs can ensure that productive work results more often than not.

Don’t incentivize LARPers

What leaders and managers should not do is look toward the peripheral aspects of work to determine productivity. Live action role-playing—or LARPing—is when a person or group of people participate in activities that have particular rules and aesthetics. Originating from a tabletop gaming context, the term means playing a game of pretend. An over-reliance on the trappings of work is a surefire way to get workers to take up LARPing their job.

Requiring proof that workers are working their designated hours is a distraction from those employees channeling their energy into actual productive work. Doing so is selecting for and incentivizing individuals who are skilled at pretending to work. It’s also an easy way to create a dysfunctional workplace, one that encourages deception, finger-pointing, and the opportunity for unscrupulous individuals to take credit for others’ work.

Avoid the normalization of overworking

For organizations that still operate under the paradigm of profit maximization and shareholder supremacy, many employees are subjugated to stressors and on-the-job demands that lead to stress and poor health. Overworked and over-stressed employees simply don’t have the energy to maintain long-term productivity.

A 2019 meta-analysis examined the effects of long working hours on health and showed that overworking leads to poor physical and mental health, and an increase in all-cause mortality. With all of the associated health risks from overworking, it’s clear that having employees work more can backfire and lead to reduced productivity over time. Putting in more than 50 hours of work in a week is effectively pointless.

A focus on employee supremacy, on the other hand, invigorates workers and makes work-related stress feel much more manageable. Your management efforts should be on managing your employees’ energy and ensuring their most focused hours are protected as much as possible. Our attention cannot be consistently in a state of focus, our brains were designed to be distracted. Factoring in the need and susceptibility to falling into distractions, how productive can we really be on any given day?

According to research conducted by the time tracking software RescueTime, only an average of 2.5 hours of focused productive work is logged in front of a screen each work day. A 2016 study in the UK revealed a similar result with respondents indicating an average of just under three hours of productive work each day. To be fair, both studies acknowledge that workers also completed standard work tasks every day, such as scheduling and attending meetings, and answering work-related emails and texts, that are more typical than transfixing.

That being said, you should look toward the structure of your workplace to be sure that opportunities for intense, focused work aren’t being crowded out by administrative and social activities. There’s only so much work that can be accomplished each day, but the solution to achieving consistent productive work isn’t by assigning more working hours above the expected 40.

Getting smart about productive work

The expectations placed on us by our personal lives and our workplace often have us navigating and making sense of a constant deluge of information. Experiences of information overload are a common sentiment. While digital technologies are often the main contributors to this issue, there are also many tools and strategies available to combat information overload.

One approach for organizing digital information is the The PARA Method. The core of this system is to parse out the information you encounter into one of four categories: projects, areas, resources, and archives. Using the PARA method for personal knowledge management is how it’s intended, but scaling it to teams or departments can be a boon to productivity if there’s enough buy-in.

Another way to combat information overload and other common pitfalls at work is to ensure that you’re not setting work goals that will make you and others miserable. Assess the expectations you have for work and be certain that they are SMART: specific, measurable, actionable, responsible, and time-bound.

- Specific: What specific tasks and activities are needed to sustain the organization’s survival in bad conditions (as opposed to ideal or preferred conditions)? Starting with the specific, necessary accomplishments will help establish goalposts during the process, and help identify when workers are going above and beyond.

- Measurable: Which metrics should that work be measured with to provide the minimum necessary insight? Measuring and incentivizing “hours worked” will, in a vacuum, promote behavior where workers focus on the appearance of work rather than the actual tasks to be accomplished.

- Actionable: How can that work be broken up into intermediate steps so that it’s worked on with attention and focus distributed consistently? Work should, more often than not, be a series of accomplishments that have clear delineations as to their completion.

- Responsible: What is the minimum number of people necessary for a task, milestone, or project to be completed? Adding additional workers, checkpoints, and communication bottlenecks will not likely improve the speed of completion unless each additional person handles a well-defined portion of the work.

- Time-bound: When is the specific deadline for the work? Project a time line that includes considerations discussed in this article, in particular the fact that people on average generate 90-120 minutes of productive work once or twice a day (and only if that time is dedicated to that work and free from distractions).

For more on the SMART system, here’s a short adaptation of Randy J. Paterson’s book, “How to Be Miserable”, which demonstrates that many common approaches to life lead to misery rather than success (so it’s best to learn what they are so you can avoid them).

Productivity is when work is consistent and self-directed

Another way to be smart about productive work is to approach changes to yourself and to your organization in small increments achieved over time. It’s difficult to get a large group of people to be compliant with big changes to their thoughts and behavior for the same reason that it’s difficult to make those same changes within yourself; it’s due to neuroscience. The brain has a hard time adapting to change unless it is self-directed and accomplished consistently.

When it comes to improving the productivity of yourself and others, you must look at all the influencing factors. The organizations that focus on supporting their employees in a dynamic and systematic way will be more resilient and have an easier time adapting to disruptive changes to their workforce.

This is Part 6 of a series. Part 1 is on personal productivity and self-improvement. Part 2 is on competency, collaboration, and culture. Part 3 is on organizational wisdom. Part 4 is on heuristic cognition. Part 5 is on empathy and emotional intelligence. Part 6 is on physical and social needs.

Looking for more insights?

We just launched the inaugural issue of our quarterly e-mag: Digital Life. This first issue, titled “Insights on personal digital wellness,” is our latest response to the relentless expansion of information technology into our daily lives. IT is everywhere, increasingly dissolving the boundaries of digital lives on the job, off the job, and in the world at large. Explore topics such as wearable tech, data hoarding, the metaverse, and the future of work. We look forward to exploring other topics and angles in future releases.